In the history of cricket, wicket keepers’ infrequent bowls. Such moments came when captain see no chance of Test match result. Such type of moment came when Australian great wicket keeper Rodney Marsh Bowling vs Pakistan in the 2nd Test at Faisalabad March 1980. The match was heading towards a dull draw. So, Rodney Marsh bowls like a lollypop offers to batsman. In those era of cricket, pitches were often made slow and dead to draw the matches. In this entire career Rodney Marsh sent just 72 balls giving away 54 wickets without having any test wicket. So, it’s a perfect fun moment for cricket fans to relish the vintage memories.

Thursday, 2 October 2025

Thursday, 25 April 2024

Michael Slater's Masterclass vs. South Africa 2nd Test at Sydney in 1993-94.

Throughout his career, Slater was susceptible to the "nervous nineties": of the 23 times he reached a score of 90 in a Test inning, he was dismissed nine times before reaching 100. Michael Slater played 74 Test matches and 42 one-day internationals for Australia. He was a part of the Australian squad that finished as runners-up at the 1996 Cricket World Cup. A specialist right-handed batter as well as a very occasional right-arm medium-pace bowler, Slater represented the New South Wales Blues in Australian domestic cricket and played English county cricket with Derbyshire. Fanie De Villiers was declared player of the match for 4 for 80 and 6 for 43. His performance was against a strong team, away from home, and while defending a very low target. The match umpires were Bill Sheahan, and Steve Randell, as Tv umpire Ian Thomas and match referee Jackie Hendricks. This was test match # 1243.

Saturday, 1 April 2023

Simon O'Donnell, a multi-talented cricketer

Simon O'Donnell, a multi-talented athlete, forsook a promising career in Australian Rules football in favor of cricket. He subsequently became an indispensable all-rounder for the Australian one-day team and was a member of the squad when it made a resurgent mark with an unexpected victory at the World Cup in 1987. O'Donnell is chiefly recalled for a series of explosive innings in the middle-lower order.

During the one-day side's tour of New Zealand in 1990, O'Donnell enjoyed a career-best performance, taking 5 for 13 against New Zealand at Christchurch in the Rothmans Cup and scoring 20 runs off 19 balls with the aid of 2 fours. Despite this superlative all-rounder performance, he was not named man of the match; instead, Dean Jones received the honor for scoring 107 runs off 143 balls. Australia won the match by a resounding 150 runs.

O'Donnell was elected international cricketer of the year in 1990–91. He recovered from injury to rejoin the Australian one-day team in the 1988–89 season and played 43 more limited-over matches until December 10, 1991, claiming 56 wickets and producing 5 match-winning 50-plus scores, including the fastest half-century in One Day Internationals (18 balls vs. Sri Lanka in Sharjah, 1990). O'Donnell maintained a highly impressive batting strike rate of 80.96 runs per 100 balls in ODIs, nearly double his scoring rate in Tests.

Between 1984 and 1993, O'Donnell played for Victoria in the Sheffield Shield as an all-rounder, scoring a century in his first match. He played 6 Test matches in 1985, 5 on the Ashes tour of England and one at home, but he was more successful in the shorter form of the game due to his low bowling strike rate in five and four-day cricket. He was viewed as a limited-overs specialist with clever medium-paced bowling and explosive lower-order hitting. He participated in 87 ODIs from 1985 to 1992, scoring 1242 runs and taking 108 wickets in his career. He played a significant role in Australia's victory in the 1987 World Cup Final, taking a large number of wickets and ending the tournament as Australia's most economical bowler. Shortly after, however, he began to experience severe pain and was diagnosed with cancer. O'Donnell made a strong recovery and returned to one-day international cricket from 1988-89.

His clean, powerful drives straight off the wicket and through mid-on were particularly effective. However, O'Donnell's intelligent fast-medium bowling often proved to be more pivotal in Australia's one-day fortunes. Since he retired from cricket, O'Donnell has joined the Nine Network's commentary team and is the regular host of The Cricket Show, which airs during the lunch breaks of Tests in Australia.

Saturday, 25 July 2020

Warwick Armstrong bowled two consecutive overs in the same innings in a Test match

Wednesday, 15 January 2020

Bill O’Reilly’s - One of Best Leg Spinner Australia Ever Produce

Monday, 13 January 2020

Keith Miller, Australia 1946-1956

Tuesday, 7 January 2020

Adam Gilchrist 1999–2008

Adam Gilchrist must be one of the most fearless cricketers of all time. It is all very well swinging the bat seemingly without a care in the world at the county or state level. It is quite another to do so when a Test match or even a one-day international hangs in the balance. But all games appeared to come the same to Gilchrist. He was naturally aggressive left-hand batsman, widely regarded greatest wicket-keeper the batsman in the history of cricket.

Adam Craig Gilchrist is born on 14 November 1971 at Bellingen in New South Wales, Australia. And he played in a very strong Australia team. Although it is true, and one that was often expected to win with something to spare. But Gilchrist played the same for every team he represented, and in all situations.

If he had an advantage, it was in not starting his Test career until a relatively late stage. He made his first-class debut in 1992 and perform consistently till 1996. Eventually, Gilchrist debut ODI in India in 1996 and then a few days short of his 28th birthday when he finally got his chance, having been kept waiting for his opportunity by Ian Healy, a fine keeper and capable enough batsman to average 27 in Tests.

He made Test debut against Pakistan at Brisbane Gabba scored 81 off 88 balls before bowled by Shoaib Akhtar and in his second retrieved a dire situation in spectacular fashion. Gilchrist had spent three years in Australia’s one-day team and already made a considerable mark as a destructive opening batsman with several hundred to his name.

He thus arrived conscious that there might be few second chances but also experienced enough to know his own game. Australia, set 369 to win against powerful Pakistan bowling attack, were apparently heading for defeat to Pakistan in Hobart when Gilchrist joined Justin Langer at 126 for five seems almost lost. Gilchrist showed a real class to smashed Wasim Akram, Waqar Younis, Shoaib Akthar, Azhar Mehmood, and Saqlain Mushtaq.

Cool as you like, the two of them all but took their side home, Justin Langer falling with five runs still needed. Gilchrist finished unbeaten on 149. Quite a few of Gilchrist’s best innings came when Australia was in difficulties rather than when they already had a big score on the board by the time, he strolled out at number 7. Adam Gilchrist said; he enjoyed it more when they were in trouble because it gave him something to work with. Not that he could not drive home good positions either.

When he went in at Johannesburg in 2002 against South Africa, when Australia wasn’t a difficulty at 293 for five and he proceeded to smash what was then the fastest Test double century on record. Gilchrist smashed 204 runs off 213 balls including 8 towering sixes and 19 rolling shots over the boundary.

Australia won the match an innings and 360 runs. Further, in the next match at Cape Town, he took South African bowling to knee scoring another hundred 138 runs off 108 balls in just 172 mins including 22 fours and 2 sixes. Australia owed its strength to many things, but Gilchrist’s presence was surely a crucial factor in their dominance around the turn of the century.

Australia won an astonishing 73 of the 96 Tests he played between 1999 and 2008 and lost only 11. One of those defeats came when Gilchrist himself, acting as stand-in captain for the injured Steve Waugh, made a rather too adventurous declaration at Headingly in 2001. In this Ashes series, Gilchrist again top of his game, scoring 340 runs at 68 including 26 dismissals and Australian won the Ashes 4-1.

Adam Gilchrist finished on the winning side in each of his first 15 Tests. He also played in three winning World Cup finals in 1999, 2003 and 2007. Gilchrist contributed runs on each occasion, most dazzlingly at Barbados in 2007 when in a game reduced to 38 overs aside, he rattled up 149 off 104 deliveries against Sri Lanka. Some of his knocks were just unbelievable and still in people's minds.

The record of this lean, slightly built left-hander was remarkable and leaves him towering above all other international keeper-batsmen. In Tests, he hit 17 hundred and averaged 47.60, highly impressive figures when it is borne in mind what a toll hour spent behind the stumps takes on mind and body. Most remarkable though was his strike rate of 81.95, which places him second only to Virender Sehwag.

In 2007, he was a member of the Australian team who took part first-ever T20I world cup in South Africa. In this tournament, he scored 169 runs at 33.80 as Aussies were knockdown by India in the Semis. He was also the first batsman to hit 100 sixes in Tests. Moreover, against England he scored a super-fast hundred in just 57 balls at Perth, missing Richard long time 56 balls hundred. Later, Pakistan Misbah-ul-Haq equaled in 56 balls and then broken by Brendon McCullum.

He hit 16 hundred in one-dyers, in which his strike rate of 96.94 again puts him second only to Sehwag among bona fide batsmen. In that format, he stands tenth on the six-hitting list with 149. Needless to say! that Adam Gilchrist was a big success when he joined the first wave of players recruited to the Indian Premier League in 2008.

Among Test keepers whose careers are complete, only Andy Flower, who averaged 53.70 but batted in far less explosive fashion, can approach his record. Matt Prior, Les Ames and Kumar Sangakkara is among the few to even average more than 40. It has been the fate of every international keeper since to be measured against him. Every team searches not just for a competent glove-man but a cricketer who can also bat and score regular hundreds.

Gilchrist set the mark and others strive to meet it as best they can. In fact, several keepers have done very well without quite adhering to the Gilchrist blueprint of reliable runs delivered with all-out aggression – Matt Prior for England, MS Dhoni for India, Kumar Sangakkara for Sri Lanka and Brad Haddin for Australia have all had their moments, while AB de Villiers maintained his batting form amazingly well after temporarily taking over the gloves from Mark Boucher in 2012.

But the greats do it time and time again and that is what sets Gilchrist apart. Gilchrist played his early cricket in New South Wales but with the state already having an established keeper he moved to Western Australia in his early 20s. There, like many batsmen brought up on the hard surfaces in Perth, he developed into a strong cutter and puller of fast bowling.

The one team against whom his record was iffy was India, whose spinners Anil Kumble and Harbhajan Singh managed to keep him largely, if not totally, in check. A few fast bowlers, notably Andrew Flintoff bowling at his absolute best in 2005 Ashes, managed to deny him the room to free his arms by coming around the the wicket at him and firing the ball into his body, but it was a plan requiring perfect execution.

In the next Ashes series, in Australia in 2006–07, Gilchrist exacted brutal revenge, splattering the English bowling to all parts of Perth in what was then the second-fastest Test century of all time. Gilchrist also developed into a considerable keeper. He had to keep to Shane Warne a lot, so in common with a lot of keepers of the the modern era, like Ian Healy and Alec Stewart, he improved himself enormously through necessity, exposure, and hard work.

Again, he had the advantage of working for the most part with one of the most formidable bowling attacks in history, but in the main, his standards were very high. When he retired, he had a record 416 Test dismissals to his name, an impressive haul in only 96 matches. ‘Gilly’ also played the game in a good spirit and earned a reputation, very unusual in the modern game, of being a ‘walker’.

Adam Gilchrist held most dismissals by a wicket-keeper in ODI, which is being broken by Kumar Sangakkara in 2015. As an Australian captain, in the six Test matches, four was won, one lost and one draw. In 17 ODI’s 12 won, 4 lost, and one was ended without being a ball bowled. In two T201, he won one match and lost one.

Adam Gilchrist was a regular team member was rarely available for domestic matches from 1999 to 2005. Hence, he could not have enough time to play for his state. He made only seven first-class appearance for his local state. Adam Gilchrist retired from test cricket in March 2008, but he keeps on playing domestic cricket until 2013.

He appeared in six IPL seasons, three for Deccan Chargers, and three for King XI Punjab. He was named Wisden Cricketer of the Year in 2002 and following year awarded the Australian Allan Border Medal. Gilchrist left unbelievable mark on the whole cricketing world. In 2013, he was included in the prestigious ICC Hall of Fame.

Some of Adam Gilchrist best performances in different versions are.

Test Cricket - 204* vs South Africa at Johannesburg in 2003

ODI Cricket – 172 vs Zimbabwe at Hobart in 2004

T201 Cricket – 48 vs England at Sydney in 2007

First-Class - 204* vs South Africa at Johannesburg in 2003

List-A Cricket – 172 vs Zimbabwe at Hobart in 2004

T20 Cricket - 109* Mumbai Indians vs Deccan Charges in 2008

He was famous for walk batsman, on numerous occasions he walked even umpires given Not out. Gilly reignite the debate during a high-pressure match against Sri Lanka in the semi’s of 2003 world cup, after the umpire ruled him not out, but he walked straightforwardly. Even in Bangladesh, he walked when TV umpire didn’t find any contact between bat and pad, but he walked. The integrity of the game was so close to him.

Saturday, 14 December 2019

Ray Lindwall Australian Premier Fast Bowler 1946–60

Ray Lindwall suffered a dip when England regained the Ashes in Australia in 1954–55 but within weeks was back among the wickets in the Caribbean, where he also scored one of his two Test centuries. Lindwall was a more than useful lower-order batsman although in what was generally a strong and successful side – Australia lost only nine of the 61 Tests in which he appeared – runs were rarely needed from him.

Ray Lindwall suffered a dip when England regained the Ashes in Australia in 1954–55 but within weeks was back among the wickets in the Caribbean, where he also scored one of his two Test centuries. Lindwall was a more than useful lower-order batsman although in what was generally a strong and successful side – Australia lost only nine of the 61 Tests in which he appeared – runs were rarely needed from him.Wednesday, 11 December 2019

Richie Benaud Australia, 1952 – 1964

Sunday, 8 December 2019

Don Bradman Australia, 1928 – 1948

Indeed, the greatest batsman ever born in the history of cricket. His figures and feats are ones with which you simply cannot argue. Don Bradman record is so far ahead of anyone else’s that one can scarcely believe one man could be so dominant through a career spanning 20 years.

Whereas most players, if not every other player but him, went through dips in form, he maintained his supremacy each year, every year. That was what really set him apart. As Wally Hammond said, Don Bradman whole career demonstrated his merciless will to win. One can only admire the mental strength he must have possessed.

As with WG Grace, it often became a match between the opposition and him. ‘He spoilt the game,’ Jack Hobbs said. He got too many runs.’ Australia lost only two series in which he played. Both were against England. The first was in 1928–29 when Don Bradman was appearing for the first time and was dropped for one game after making an innocuous debut (his response when he was recalled was to score two hundred in the remaining three games).

The second came in 1932–33 when Douglas Jardine deployed his infamous Bodyline tactics. That series represented Bradman’s most serious failure and yet he averaged 56.57! Although, that’s wasn’t true failure in other people’s books. These were the only two series in which he averaged less than 70. You’ve seen brief glimpses of footage of him batting and wondered about some of the field settings, which hardly seemed designed to slow down the scoring.

He himself has conceded that the game in those days was in some respects very different from the way it later became. When Shane Warne and Sachin Tendulkar were granted an audience with him in the 1990s. An interesting conversation ensued in which ‘The Don’ was asked how he might have fared in the modern era.

He said he would not have scored so many runs exactly because of defensive fields; in his day, fields remained attacking for far longer, even when batsmen were scoring quite freely. There was no such thing as a deep point or sweeper in those days and he also conceded that the standard of fielding was much better in the modern game.

His admission that he might have averaged nearer 70 than 100 had he played in the modern era prompted some jokes along the lines of ‘Not bad for a 90-year-old’, but his comment was perhaps a serious and revealing one. To an extent, the transformation in fielding standards supports to explain one of Bradman’s key strengths, which was the phenomenal speed of his scoring.

Don Bradman two Test triple-centuries were both scored in matches in England restricted to four days. The first one in 1930, when he brilliant scored 309 of his 334 runs in one day, including a hundred in each of the three sessions. In that series, consisting of four matches lasting four days and one (the last one) played to a finish. He scored 8, 131, 254, 1, 14, 334 and 232 for an aggregate of 974 which still stands as the record for any series, even though many series since have been played over more matches and more days.

That innings of 334 was at the time the highest ever played in a Test match and meant that he held the records in both Test and first-class cricket, having earlier that year scored an unbeaten 452 (in just under seven hours) for New South Wales against Queensland in Sydney. He was just 21 years old at the time.

His personal view was that his innings of 254, made in the second Test at Lord’s, was the best of his career. For him, though, scoring fast did not mean taking foolish risks. His method was so clinical and efficient – if not always pretty enough for some purists – that he hit few sixes and rarely hit the ball in the air (he had an unorthodox grip that did not lend itself to aerial shots).

And even if we concede that the standard of fielding was not as high then as it is now: it was the same for everyone in his time and he still stood head, shoulders and a fair bit of the body above his peers in terms of productivity. He was clearly an interesting character. Talk to the likes of Ian Chappell, who knew The Don well, and what comes back is not all sweetness and light. He appears to have been prickly and critics will call him self-centered and self-interested.

It was well known at the time that Don Bradman did not see eye to eye with several other Australian players, the Irish-Australians Bill O’Reilly and Jack Fingleton among them. When Australia – without Bradman, who was recovering from illness – happily toured South Africa under Vic Richardson in 1935–36, only for Don Bradman to be appointed captain in his place for the following winter’s series against England, it was not a popular decision with all parts of the dressing room.

But Don Bradman proved as ruthless and as successful a captain as he was a batsman, and the results brooked little argument. A classic example of his leadership style came in that 1936–37 series against England when he reversed his batting order on a rain-affected wicket so that by the time he went in, at number 7, conditions had improved, and he was able to score what proved to be a match-winning 270.

His contribution went beyond just the playing feats. He also had a role in management and was a very influential member of the Australian board. Some feel he might have done more to see that players were better remunerated in the period leading up to their decision to take Kerry Packer’s dollars, but he also played an undeniably beneficial role in eradicating ‘chucking’ and in encouraging the teams to play enterprising cricket ahead of the famous 1960–61 series between Australia and West Indies.

With a similar ambition in mind he was also instrumental in Garry Sobers, the world’s biggest drawcard, joining South Australia the following year. I met him briefly once in Adelaide on one of my early tours, a chance encounter walking round from the dressing rooms to the dining room. He was struck by how small he was, a reminder that many of the finest batsmen – Sachin Tendulkar, Brian Lara Ricky Ponting, and Sunil Gavaskar also come to mind – are not great hulks.

He was 5ft 8in tall and not powerfully built. You imagine that when you meet such a revered figure there will be a golden aura surrounding them, a great charge of energy when you shake hands, and pearls dropping from his lips when he speaks. He exuded coolness, calmness and a normality that hid the great ability and determination. One of the first cricket books I ever read, and pored over, was his masterly Art of Cricket.

While it is hard to compare different societies and different times, Bradman carried the hopes of a nation on his shoulders, just as Tendulkar did for Indians in a later era. In Bradman’s case, Australians were feeling acutely the consequences of the First World War, which had left their relationship with Britain under strain, as well as the Great Depression. Sport gave them an identity and Don Bradman provided them with their most reliable champion.

But the burden took its toll, which only makes his achievements more remarkable. Bradman himself said that his concentration was what set him apart from others. He was famously single-minded in practice as a child, using a single stump to hit a golf ball against a water tank outside the family home in Bowral in rural New South Wales where he grew up, the fifth child of a wool trader and carpenter.

He was 17 years old when he made scores of 234 and 300 for Bowral, the former against a young O’Reilly (off whose bowling he was dropped twice before reaching 50). This led to an invitation to attend a practice session at the Sydney Cricket Ground, and ultimately to an offer to play for the St George club.

Don Bradman and Stan McCabe 1938

Don Bradman and Stan McCabe 1938In his first match for them – and his first-ever match on a turf wicket – he scored 110. A little more than a year later he was playing his first match for New South Wales and scoring another hundred. What was particularly striking was how Bradman was equal to each new challenge that was presented to him. He made a success of his first season of state cricket and his first season as a Test cricketer, despite being dropped after one game.

When doubts were expressed that he would struggle in English conditions on his first tour in 1930 his response was to hit 236 at Worcester in his first match and he went on to make 1,000 runs before the end of May. Such indeed were his powers of concentration that he was never out in the 90s in Test cricket (he scored 29 hundred).

He was surely fortunate to play in an era tailor-made for batsmen. Scoring in state cricket in Australia was huge and before Bradman had arrived on the scene Bill Ponsford twice played innings in excess of 400. Far fewer Test matches were played in those days but even so three other batsmen besides him made Test scores of more than 300 in the 1930s.

In the series in which Don Bradman made his debut, Wally Hammond topped 900 runs. Bradman therefore had plenty to aim at in terms. Just how well he succeeded can be measured by a first-class career average of 95.14 and career Test average of 99.94, which remain well ahead of all his rivals. He played at a time when big scores – huge scores – were a necessity, and Don provided them like no batsman before or since.

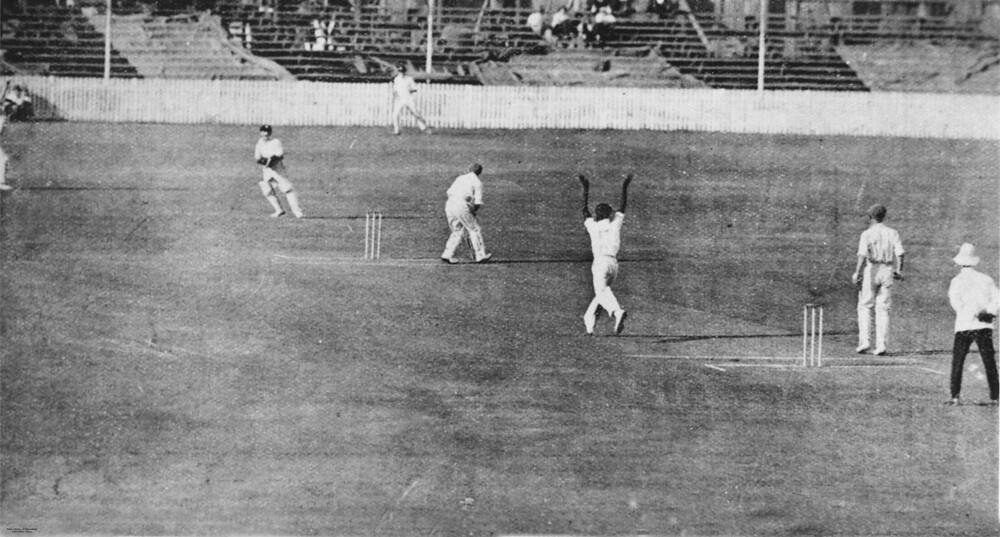

Eddie Gilbert and Donald Bradman at the Woolloongabba

Eddie Gilbert and Donald Bradman at the WoolloongabbaRead More

.jpg)