Just his personal statistics were enough to inspire anxiety at the prospect of facing Joel Garner. At 6ft 8in, few bowlers have stood taller, and with those great big long arms and mighty levers of his, not many grounds had sightscreens big enough to accommodate the top of his bowling arm.

Joel Garner was phenomenally accurate, but the one word you had to focus on was ‘bounce’. You were always looking at a length ball from him and thinking: ‘How high is this going to bounce?’ ‘High enough’ was mostly the answer. Although he could generate bounce, though, or perhaps precisely because of it, there was great danger in the balls he bowled of fuller length.

A lot of his wickets – almost half in Tests, in fact – were bowled or leg-before, the batsmen no doubt worrying about the ball that might threaten the glove or head only to find one homing in on their stumps instead. Garner was a great purveyor of the Yorker, the old sand-shoe crusher or big toe breaker.

The Yorker is a delivery that modern-day batsmen have found ways to lever to the boundary in one-day cricket but in Garner’s day we were happy just to keep it out, whatever the game, whatever the situation. You might be doubt very much if even today batsmen would be hitting him for six if he got his Yorker in. He was quicker than people thought.

If he wound it up, he wasn’t far behind Michael Holding and Andy Roberts in pace. That wasn’t always his role though. The West Indies bowling was so strong that some of them – and Joel was one – inevitably had to fulfil roles they would not have done had they been playing in almost any other side.

He started his Test career in 1977 but it was not until 1984 that he took the new ball, Clive Lloyd preferring to use him as something of a stock bowler. But once the new ball was his, Garner became even more potent than he had been.

Somerset naturally used him differently when he played for them and he helped them win trophies with some explosive bursts. The first time I faced him in a major encounter was in the World Cup final of 1979. It was not to be my proudest moment. That was decidedly up against it, chasing a big total and already well behind the rate required, and Joel was hardly the man to give you something to play within that situation.

Giving room to try and carve one through cover just gave him a sight of many stumps. Several England batsmen were out for zero, bowled, one of five wickets he took in the space of 11 balls as the game sped to its conclusion. Amazingly four England batsmen were bowled, the other caught behind.

How to score runs off him was a big puzzle for us as aside. England faced him again a few months later in a one-day series in Australia without making much headway and when faced with him for the first time in Tests in England the following year his control was incredible. In the first Test he bowled 57.1 overs off which just 74 runs were scored (at a cost of seven wickets); in the second, 39.3 overs for 57 runs (and six wickets).

It was some small crumb of comfort to England, having been dropped after the first game, to see that others found him no easier to play. Over the course of the five Tests, he sent down 212.4 overs for 371 runs and 26 wickets. His metronomic capabilities should not be overstated, however.

Every blue moon there might be something you could have a go at. He might sometimes give you something outside off stump you could flail at, or something short you could try and help over the slips. He played in the Jamaica Test in 1981 in which Graham Gooch and David Gower both scored 150s.

It was a quick, bouncy pitch but fortunately it was also true in its bounce. Somehow, England found away on that occasion. He came into the West Indies side as a stand-in for a home series against Pakistan in 1977 and was an instant success. He took 25 wickets in five matches, although there were tell-tale signs that he still had things to learn.

His wickets cost 27.52 each and went at more than three runs an over. These were expensive figures for Joel. Of the 14 series, he subsequently played, his average strayed over 23 only four times and his economy rate over three runs per over only twice. He was very, very consistent. He was also a fine catcher around the slips and gully.

He was perhaps fortunate to arrive on the scene just as West Indies were reaching the peak of their collective powers and finish in the late 1980s before the decline in Caribbean cricket had begun. Remarkably, he played in only five defeats in his 58 Test matches (in which he took 259 wickets at an average of just 20.97).

A lot of that was down to his reliability but of course, he was playing in a side with very few weak links. To be part of the most feared pace attack of all time almost automatically qualifies you to be one of the great individual bowlers. They were all immensely skillful as well as quick, and all decent men too.

As a bloke, Joel was a particularly lovely guy, with those big genial eyes of his and that typically Bajan air of laid-back affability. He was known as ‘Big Bird’ not just by his own team but by everyone. There was a lot of affection for him, if not for his bowling.

Read More

- Sir Conard Hunte – The Greatest West Indies Batsman

- Sylvester Clarke – A Bowler to Have on Your Side

- Allan Rae – Classy Unsung Opening Batsman

- Roy Gilchrist – A Violent Temper Fast Bowler

- Roy Fredericks – Great West Indies Left Handed Batsman

- 50,000 Runs in all forms of cricket

- Viv Richards West Indies, 1974 –1991

- Malcolm Marshall – Most Persuasively of all Windies Peers

Don Bradman and Stan McCabe 1938

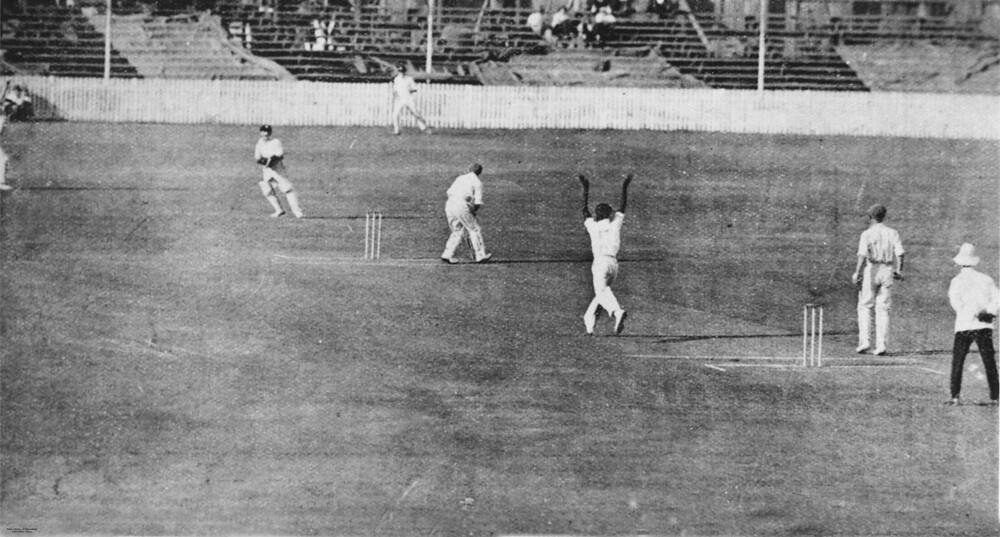

Don Bradman and Stan McCabe 1938 Eddie Gilbert and Donald Bradman at the Woolloongabba

Eddie Gilbert and Donald Bradman at the Woolloongabba